Why We Still Don’t Have Reliable Exercise Guidelines for Women After 150 Years of Research

The truth about hormones, research flaws and why women deserve better

The study of the menstrual cycle and exercise has been happening since at least 1876.

This was when Professor Mary Jacobi won the Harvard University Boylston Prize Essay. Her study looked at how menstruation affects physical work and the need for rest.

And yet, almost 150 years later, there are still no guidelines for fitness and nutrition specifically for women.

We could blame the gender data gap for this.

Where the majority of studies are carried out on men and then just applied to women.

Where females are significantly underrepresented in all human studies-in all fields.

And where men are seen as adequate proxies for women.

[Let us also not forget that there are many studies that may not ever get published]

But that’s not the only reason.

Because honestly, the research that has been conducted on women is, well, flawed.

You would think that with decades of research, consistent methods of studying women would have been developed. But you would be wrong.

That’s even with researchers in the early 2000s giving critical feedback on how women should be studied.

This paper obviously began to raise awareness of the flaws within this field. And yet this doesn’t change the fact that we are still relying on research that is inconsistent, unreliable and invalid. Even 20 years after this feedback.

The truth is, the reason these studies on women are poorly designed comes down to one thing—researchers don’t fully understand the menstrual cycle.

Understanding the complexities of hormonal changes

Oestrogen and progesterone are sex hormones. But they don’t just deal with reproduction. They affect the whole body.

They target individual tissues, including epithelial, connective, muscle, and nervous tissue. And influence biological processes. Metabolism. Breathing. The immune system. Our brain. Digestion. The cardiovascular and nervous system.

So different amounts of these hormones will “influence the mechanisms that control and regulate cell function and integrated physiologic adaptation in women.”

To put it simply, oestrogen and progesterone affect literally everything in the body.

But how they affect these different tissues and systems will depend on the amount of these hormones. As well as the combinations of hormones.

And the amount of hormones, and the combinations, change. Not only throughout a woman’s life but also every single day of her menstrual cycle.

A lack of validity

During a woman’s life, there are five main factors that will affect oestrogen and progesterone levels:

normal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle.

disruptions to the menstrual cycle caused by illness or disease, such as PCOS or endometriosis

manipulation of the menstrual cycle with external hormones such as HCPs or HRT

pregnancy

menopause (and perimenopause)

If this is not understood (or ignored) by researchers, then there are a number of mistakes that are being made. Which again makes the research inconsistent, invalid, confusing and conflicting.

Elliott-Sale et al. (2021) wrote,

The validity of studies, or lack thereof, in sport and exercise science using women as participants is rarely discussed.

What is valid for one woman may not be valid for another.

So when we read the research, we need to check that the women’s hormone and reproductive profiles actually match what we are trying to find out.

It’s like looking for injury risks in footballers by studying swimmers. They just don’t match.

The same is true for women whose hormone status is different.

Basically, we cannot compare the 16-year-old whose menstrual cycle has not yet settled, with the 30-year-old who has just given birth.

We cannot compare the 45-year-old with perimenopause symptoms, with the 36-year-old who has PCOS.

We definitely cannot compare the 60-year-old post-menopausal woman with the 27-year-old who has endometriosis.

And obviously we cannot (or should not) compare the woman taking hormonal contraceptives with the naturally cycling female.

Each of these women has a different hormone status. A different reproductive profile.

Each has different amounts (and combinations) of progesterone and oestrogen in their body.

And as we know, different amounts of hormones affect our body, mind, energy and moods in so many ways.

Yet I see this all the time when reading through the research. Or rather, I don’t see it.

Because when females are used, rarely is their hormone status or reproductive profile mentioned.

They are simply labelled as ‘women’.

The importance of considering menstrual cycle phase

Another problem is that when females are used in studies, researchers often test them only in the early follicular phase.

This is so that they can minimise the effects of oestrogen and progesterone.

Meaning when oestrogen and progesterone are at their lowest. And women are more ‘male-like’.

Less obscure, if you will. Less complex.

Sometimes the researcher has not even thought about the menstrual cycle and the effect the hormones could have on their study. And so the menstrual cycle phase is not mentioned at all. Meaning the female subjects are studied at any point in their cycle.

Hence a woman who is menstruating (↓ oestrogen & ↓ progesterone) may be compared with a woman who is ovulating (↑ oestrogen & ↓ progesterone). Or compared to a woman who is in the luteal phase (↑ oestrogen & ↑ progesterone).

But we simply cannot compare these phases. They are hugely different.

And every woman will tell you she feels completely different around menstruation compared to every other part of her cycle—regardless of what the research shows.

And this affects, well, everything.

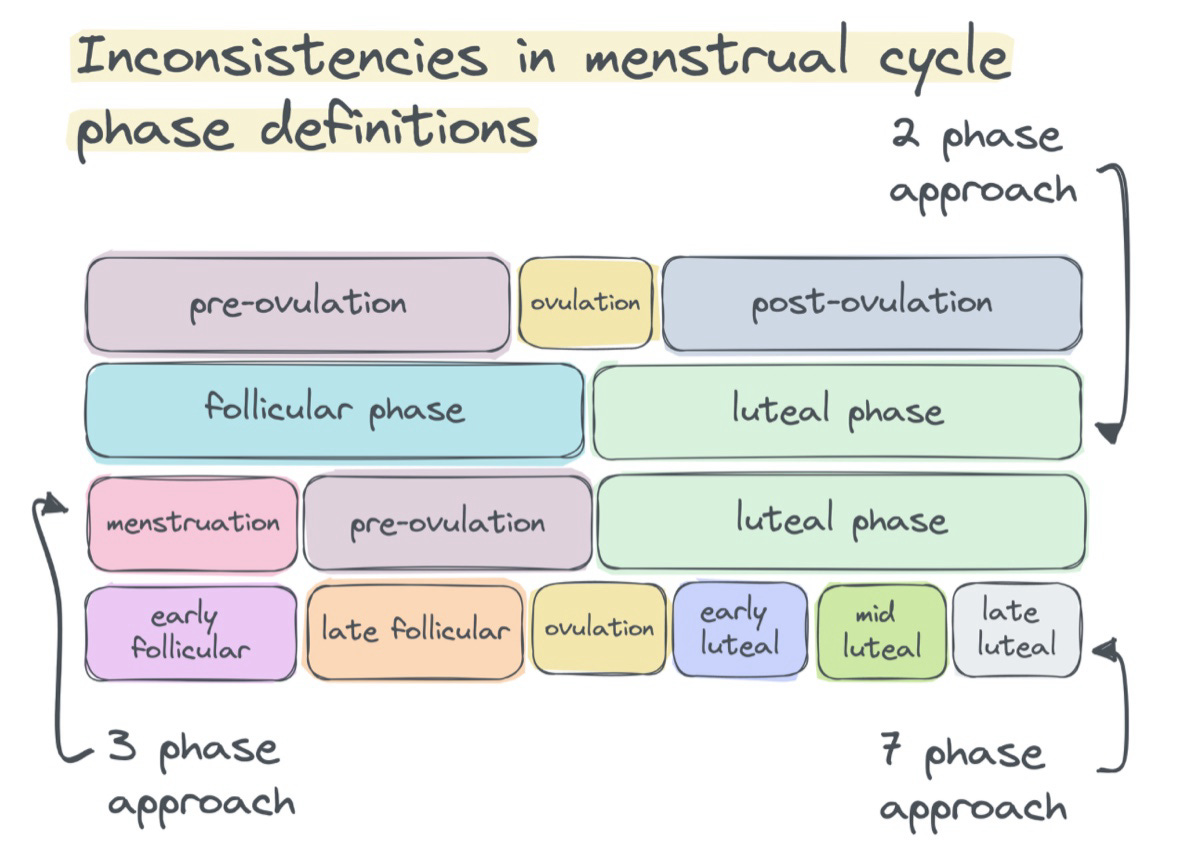

Inconsistencies in menstrual cycle phase definitions

So what about the studies that do break down the menstrual cycle phases? They’re good, right?

Actually, that’s always not the case.

After all, we cannot—or at least we should not—look at just one single study.

[I love the quote from Scott Alexander: “Aquinas famously said: beware the man of one book. I would add: beware the man of one study.”]

We need to look at multiple studies to see if they are saying the same thing. Or whether contradictions are being found.

The problem here is that research doesn’t have consistent methods of defining the different phases.

The 2 Phase Model

In the simplest terms, the menstrual cycle divides into two phases: the follicular phase and the luteal phase.

These are separated by ovulation. Not menstruation, as most people think.

These two terms are often used to describe the different phases that a woman is in. So she is either in the follicular phase or the luteal phase.

The problem?

Splitting the menstrual cycle into only two phases hides the hormonal shifts happening within each of those phases.

The 3 Phase Model

Luckily, most research does not rely on the two-phase model. Most research on the menstrual cycle focuses on a three-phase approach:

menstruation (↓ oestrogen ↓ progesterone)

pre-ovulation (↑ oestrogen ↓ progesterone)

luteal (↑ oestrogen ↑ progesterone)

But again, this comes with the assumption that hormones in these phases are static.

And guess what? They’re not.

The 7 Phase Model

Thankfully, some researchers do go deeper.

They use sub-phases like early follicular, late follicular, ovulatory, early luteal, mid-luteal and late luteal. Which is brilliant.

Because they’re starting to appreciate all the different hormone states that exist. And what that means for the research.

So am I happy with this?

Well, I would be—if every study followed the same methods and used the same definitions.

But they don’t. At least not at this moment in time.

Hence we have studies that divide the menstrual cycle into two, three, four, six or even seven phases.

Meaning there are inconsistencies in terminology and research design. And this can lead to the grouping of participants who do not match when we compare multiple studies.

It means the luteal phase of one study may not match the luteal phase of another study. And what may be referred to as “menses” in one paper may simply be labelled “the follicular phase” in another.

Obviously with the mis-match in definitions, the hormone profiles of women are mis-matched too.

The importance of accurately verifying menstrual cycle phase

As I mentioned, sometimes we are lucky enough to find researches considered the menstrual cycle. And yet, the hormonal profile of females is often implied rather than confirmed.

According to Janse DE Jonge (2019), less than half of the studies on menstrual cycle and exercise performance measured hormones.

And when hormone measurements are not used to determine the phase, researchers often use calculations instead.

This is where they use the idea that every woman is the same, each with a perfect little 28-day cycle. And on that basis, ovulation is the 14th day after menstruation.

The problem? Healthy cycles vary in length between 21 and 37 days.

This means that assuming every woman ovulates on day 14 doesn’t make sense. Not one little bit.

This often puts women in the wrong phase.

Another issue is that when researchers use calculations instead of actual measurements, women with anovulatory cycles may also be included.

These are women who do not ovulate and therefore do not produce progesterone. And so affecting results and our understanding.

The overlooked hormonal transitions

It’s important to remember that hormones are not static. Despite what we want to believe with the definitions of phases.

Of course, there are hormonal changes occurring during the transitions between phases.

But as Bruinvels et al. (2022) point out—studies often ignore this.

most of the prior research informing our practices with athletes tends to rely on a three-phased model with the assumption of steady-state hormone levels existing.

But hormones are not steady. Ever. They change. They fluctuate. Moving from high to low. From low to high. And everything in-between.

And as they do so, they challenge homeostasis. Creating a dramatic shift in the hormonal environment.

And so affecting the way a female thinks, feels and behaves.

Recommendations and efforts to improve research

It goes without saying, the complexity of the menstrual cycle is a major barrier to including women in research.

And from everything I’ve covered above, I’m sure you can understand why.

And yet, it is simply not right to exclude women from research, especially on the basis of convenience.

Thankfully, there are researchers who are doing what they can to improve future studies.

Janse DE Jonge (2019) made recommendations to verify menstrual cycle phase.

Elliott-Sale et al. (2021) guide readers to adopt good practices when working with women in science studies.

Schmalenberger et al. (2021) make recommendations to help make study results more meaningful and replicable.

Granted, there may never be a universal design for women’s research.

But we at least need to try.

Final thoughts

So, with all these issues, should we even bother looking at the research?

I believe so.

The studies may not be perfect, but they give us a place from which to start.

Even flawed research is research. And it can provide valuable insights. Ones that lead to further exploration and improvement.

Obviously, it’s important to look at any research with a critical eye. And consider the potential biases or limitations.

But dismissing it entirely would put us back in the dark ages.

Acknowledging the flaws in research can guide future studies. Giving us deeper understanding and more accurate conclusions.

Ultimately, research is an ongoing process. One of discovery and refinement.

Where each study—each piece of work—adds to our collective understanding of the world around us.

Sources

Bruinvels, G. et al. (2017). Sport, exercise and the menstrual cycle: where is the research?

Bruinvels, G., Hackney, A.C. & Pedlar, C.R. (2022). Menstrual Cycle: The Importance of Both the Phases and the Transitions Between Phases on Training and Performance.

Elliott-Sale, K.J. et al. (2021). Methodological Considerations for Studies in Sport and Exercise Science with Women as Participants: A Working Guide for Standards of Practice for Research on Women.

Janse de Jonge, X.A.K. (2003). Effects of the menstrual cycle on exercise performance.

Janse DE Jonge, X., Thompson, B. and Han, A. (2019). Methodological Recommendations for Menstrual Cycle Research in Sports and Exercise

Schmalenberger, K.M. et al. (2021). How to study the menstrual cycle: Practical tools and recommendations.